Homegrown Aquarians

Michael Metelica and the Renaissance Community remembered in film.

Valley Advocate, May 4, 2006

by Andrew Varnon

PHOTOS COURTESY OF BRUCE GEISLER

A Rolls Royce pulls up to a stop in a scene from Bruce Geisler’s documentary, Free Spirits . The camera is in tight and you see the chrome grill, the headlights and the glossy black fender. Then the camera pans back and the doors open and Michael Metelica steps out, dressed in a bright red velveteen jacket. He looks like Robert Plant with his long, golden tresses, sunglasses and orange leather pants. Then, you see that he’s stepping out onto a curb at Bank Row in Greenfield, with the Town Hall behind him. He and the band walk up to the door at the First National Bank building. This is Michael Metelica, also known as Michael Rapunzel, at the height of his powers. He is a would-be rock n’ roller, the cultish leader of a community that owns a large block of downtown Turners Falls, and the embodiment of that cultural phenomenon known as “the 60s”—both to those who saw it as a spiritual awakening and those that saw it as a decadent, materialistic bacchanal.

His story, and the story of the community he founded, is worthy of a Greek tragedy and it’s a latent history woven into the fabric of the Valley we live in. Metelica is gone—he died of cancer in 2003 in upstate New York—but there is still a core group of communards living on community property in Gill and others scattered throughout the Valley, still trying to live their lives according to the principles that drew them to Metelica’s nationally-famous hippie commune.

It’s a history that some would like to forget, but it’s one that we are lucky that Geisler—who lived at the commune for a few years—and others have labored to preserve. The film, Free Spirits , is the product of 15 years of work. Geisler said the germ of the idea was planted in him at a commune reunion. He thought it would be interesting to do a sort of flower children documentary. But he started doing interviews, and then a friend landed him a cache of archival 16mm footage, and the project grew into a full-blown history of the community.

Metelica started out as a kid from Leyden who dropped out of high school and moved out to California after reading an article about the Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang. Repelled by the violence he saw there, he returned to the Valley and in May of 1968, he built a treehouse on a farm in Leyden and moved there with a few friends. That’s where the community that was known as the Brotherhood of the Spirit began.

The film follows Metelica and the commune from its beginnings in the treehouse on Blueberry Hill through its tumultuous 20-year history, when the members paid Metelica, by then known as Rapunzel, a lump sum to leave and never come back. The commune went through several distinct phases, moving around Franklin County from Leyden to Heath to Warwick to Turners Falls and eventually to Gill.

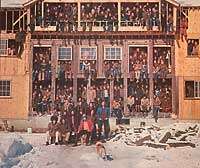

Franklin County’s most famous commune counted 350 members at its high point. Above, members crowd the dormitory in Warwick.

In its first phase, the commune was first known as the Brotherhood of the Spirit and Metelica and his followers were guided by local farmer and guru Elwood Babbit as their spiritual adviser. Many commune members look back at this time, before Babbit distanced himself from Metelica when Metelica turned away from the founding values, as the golden age. A photograph published in Look Magazine in 1970 served to popularize the commune and membership jumped from the dozens to more than a hundred. Metelica began a band in the commune called Spirit in Flesh.

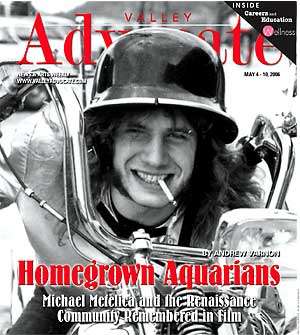

The charismatic leader Michael Metelica believed he was the rock n’ roll reincarnation of Gen. Robert E. Lee.

In 1973, Metelica changed the direction of the commune, renaming it the Metelica Aquarian Concept, and took absolute control over the running of the commune and its finances. Metelica sought to rework the community from a back-to-the-land outfit into a media-savvy entrepreneurial organization. The community purchased 35 new fuel-efficient Honda cars, audio and visual equipment and an airplane. The cars stood out in rural Franklin County and marked commune members for abuse from those who saw them as a nuisance.

Incidentally, the end of the Brotherhood of the Spirit was the subject of the Valley Advocate’s very first cover story in September of 1973. In 1974, Metelica changed his name to Rapunzel and the Metelica Aquarian Concept morphed into the Renaissance Community. Members of the community started up several businesses: a greeting card company, the Free Spirit Press, the Noble Feast Restaurant in Turners Falls and Rocket’s Silver Train, which outfitted luxury tour buses for rock n’ roll bands.

In 1975, the commune purchased the 80-acre Old Stone Lodge property in Gill and soon embarked on a project called the 2001 center, which was to be a self-sufficient community. Rapunzel began his decent into megalomania and drug use and the 1980s saw several rebellions, where several of the enterprises split off from the community and core members left. Finally, in 1988, Metelica was asked to leave and the Renaissance Community, as a commune, ceased to exist.

The wheels that peace, love and communal finances bought.

The documentary blends together photographs, newspaper clippings, interviews with former commune members and archival footage. At times, it is like watching a family home movie. At other times it is like a Ken Burns documentary with headings and quote screens interspersed with talking heads. And then there is the footage of Metelica himself in 1996, grappling with his legacy.

“We were setting ourselves apart from society because we felt society was going to collapse,” says communard Chris Garland early in the film. “We wanted to be out of it when it did, but in a position to step back in so we could put it back together. I’m almost embarrassed to say that now. It seems so innocent and foolish, that nine guys in a tree house could have an impact on the consciousness of the world.”

The energy and innocence comes through in the film. To see the hundreds of long-haired kids hanging out of the windows of the dormitory in Warwick, singing and waiving their arms, it’s hard not to look at that scene and want to be there with them, feeling what they’re feeling, that passion. Watching the movie, one gets an appreciation for the homegrown American left. It wasn’t part of a world conspiracy. It was the spirit of nine young people living in a tree house in Leyden, looking out over the hills of Franklin County and wanting to band together and find themselves.

A new-age _American Gothic_.

But thatís not how everyone saw it. The movie shows footage of an unnamed Warwick selectman, who laments that these young educated kids are wasting their resources. “With the intelligence that they have,” he said, “Instead of doing something useful for the community, they started their own community at the expense of us.” The hostility toward the community was manifested by threats and cold shoulders, but became terrifyingly real when 18-year old Peter Luban was found with his throat slashed, a case that was never solved.

Metelica is a fascinating figure, part heavy metal biker, part backwoods mystic. Many blame the downfall of the community on the cult of personality that grew up around him and how he fed off of it. Even in his later years, he seems never to acknowledge what really went on in the community, saying things like, “I allowed a lot of freedom in the community.” At one point, looking like a fallen rock star in a VH1 Behind the Music episode, he addresses the allegations of drug use. It’s a telling moment.

“Some people have this belief that I was using drugs around ‘73, ‘74, I guess,” he says. “This is not true. This is not true. There was a point, with the band, that I would occasionally use cocaine because it kept me awake and I got a lot out of it and it actually worked to do the things that I wanted to accomplish.” He says this while brushing his finger under his enlarged nose. “Like practicing eight hours a night. Yes, I did things like that. I did do that sometimes. But there was never any problems with drugs with me.”

The dozens of ex-commune members profiled in the film all have different experiences to relate about living on the commune, but there is a sense of a shared experience, a magic that was there. Jason Garland, the first child to be born on the commune in 1969, reflects, “People in the community made a great struggle and attempt at making the commune succeed. It’s sort of awe-inspiring. I feel very disappointed in my generation that they haven’t taken their beliefs and held them in high enough regard to actually try to achieve the things that they dream about.”

Metelica in later years, after the cigarettes, booze and cocaine.

Living in the Valley now, there are still scattered remnants of that dream and people who are attracted to that idea, that feeling. But there are also lingering doubts about the communes and their legacy. Although the film is about one particular commune, told largely by members of the commune, it’s an honest and compelling look at this history, definitely worth the price of admission.

« go back